As you may or may not know, I recently went back to school to get an MA in Museum Studies. While studying I had the opportunity explore an interest in medical museums by volunteering at Bethlem Museum of the Mind and The Wellcome Trust. This theme continued after I handed in my dissertation (titled “Victorian Psychiatric Photography: History, Archives, Ethics”) and began a position at the Royal London Hospital Museum in Whitechapel. It has been a wonderful first post-graduation job. I consider myself lucky to have started in a small museum because it has allowed me to get hands-on experience with many different facets of museum operation, such as cataloguing and packaging objects for storage, curating a temporary exhibit, and giving tours to school groups. Sadly, it was a short-term contract position that came to an end last week. I have learned so much about the history of the Royal London Hospital and medical collections in general. This museum is a true hidden gem. If you ever find yourself in Whitechapel, I highly recommend stopping by for a visit.

As a send-off, here are five of my favorite RLH medical objects.

1. Bernard Spilsbury Histology Slides

Sir Bernard Spilsbury was the most famous British pathologist of the 20th century. He made his mark by acting as an expert star witness for the Crown during many headline-grabbing murder trials (Hawley Harvey Crippen, The Brides in the Bath, and the Brighton Trunk Murders, to name a few). Calm, cool, and imperious on the witness stand, Spilsbury was often the determinate factor between life and death. But his obstinacy about his evidence in the face of cross-examination was a source of frustration for many of his peers in the medico-legal community. Today, scholars such as Andrew Rose are challenging the voracity of Spilsbury’s testimony and concluding that he likely sent innocent people to the gallows.

The histology slides in the store room at the Royal London Hospital Museum compliment the Spilsbury case notes held in the Wellcome Trust archive. Both collections allow modern scientists and experts to revisit these old cases. A few weeks ago, I was able to use the slides as a teaching tool when delivering a museum tour for a group of forensics students from King’s College London.

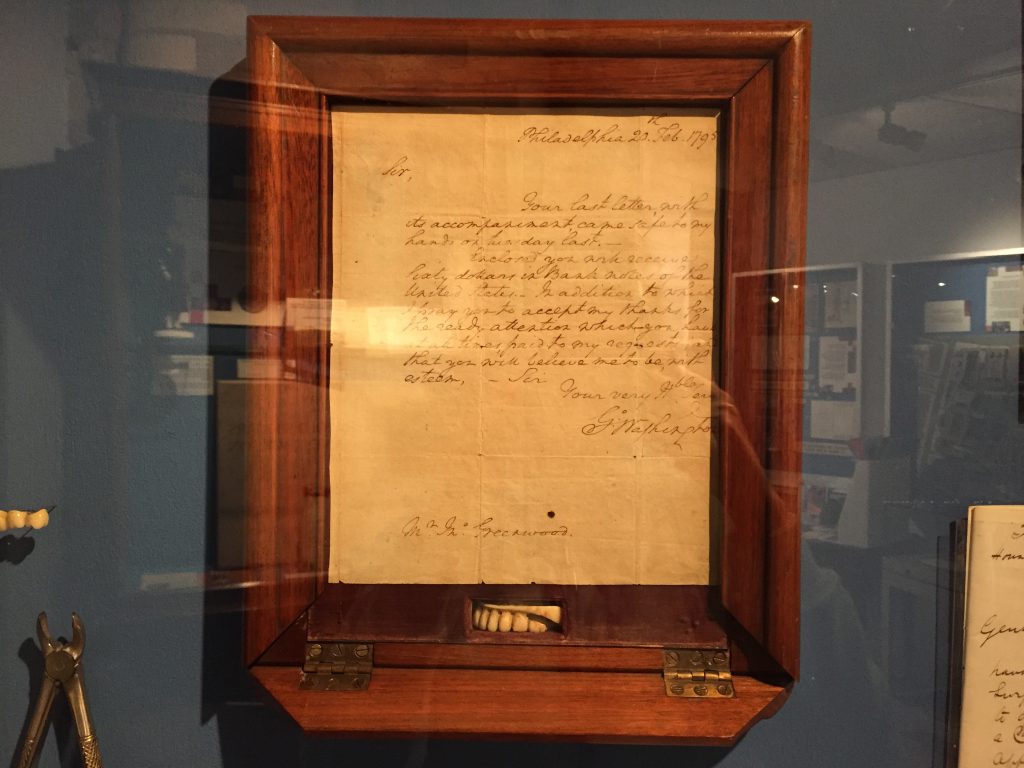

2. George Washington's Dentures

As a young child growing up in the US, I learned three things about America’s first president, George Washington: he chopped down a cherry tree, he couldn’t tell a lie, and he had wooden teeth. Imagine my surprise when I started working at the Royal London Hospital Museum and saw that one of the treasures on display was a fragment of dentures actually made for George Washington, Original American Patriot™. Out of all of the objects in that museum, Washington’s teeth are my favorite. They bring some truths to light. While Washington may very well have worn wooden teeth at some point (infections from rotten teeth were one of the leading causes of death in the 18th century), by the 1790s he was wearing teeth taken from animals and other people — possibly slaves. This pair was made of ivory by Dr John Greenwood of the London Hospital. According to the signed letter displayed along with the denture fragment, Washington paid good money for his chompers — the equivalent of about £8,600.00 in today’s money, a high price considering that wearing them was very painful.

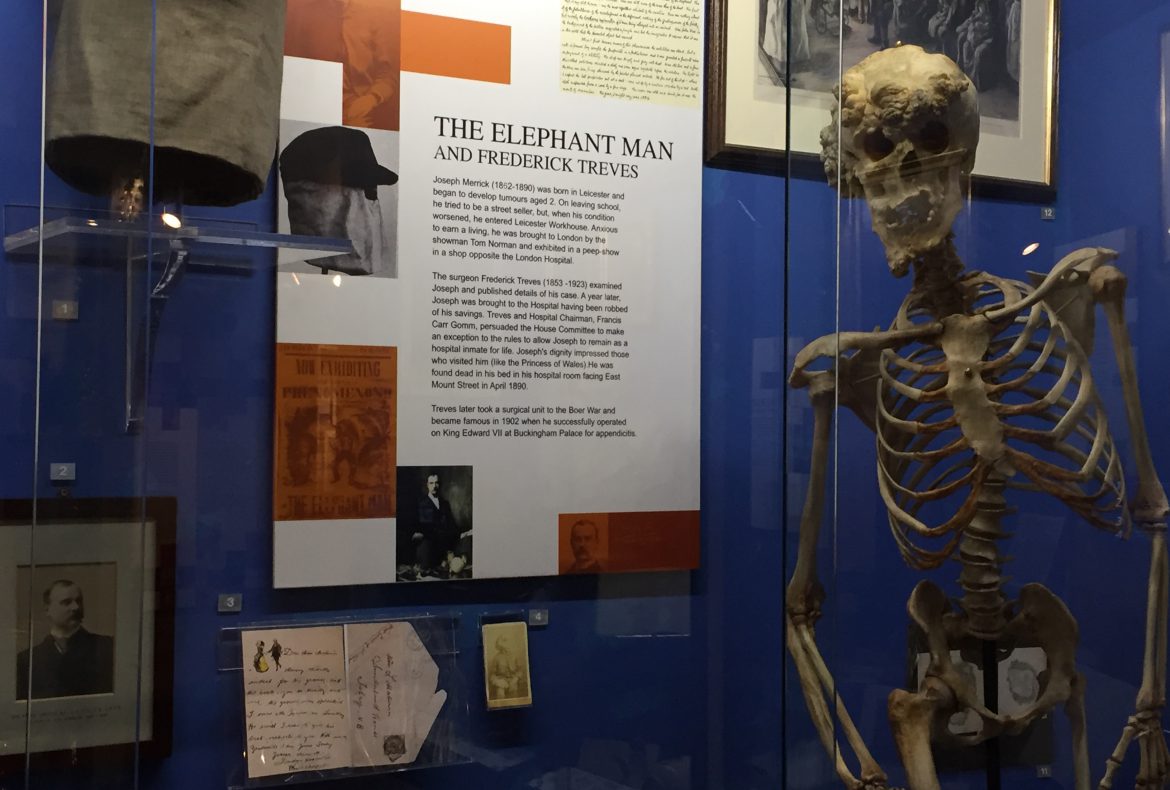

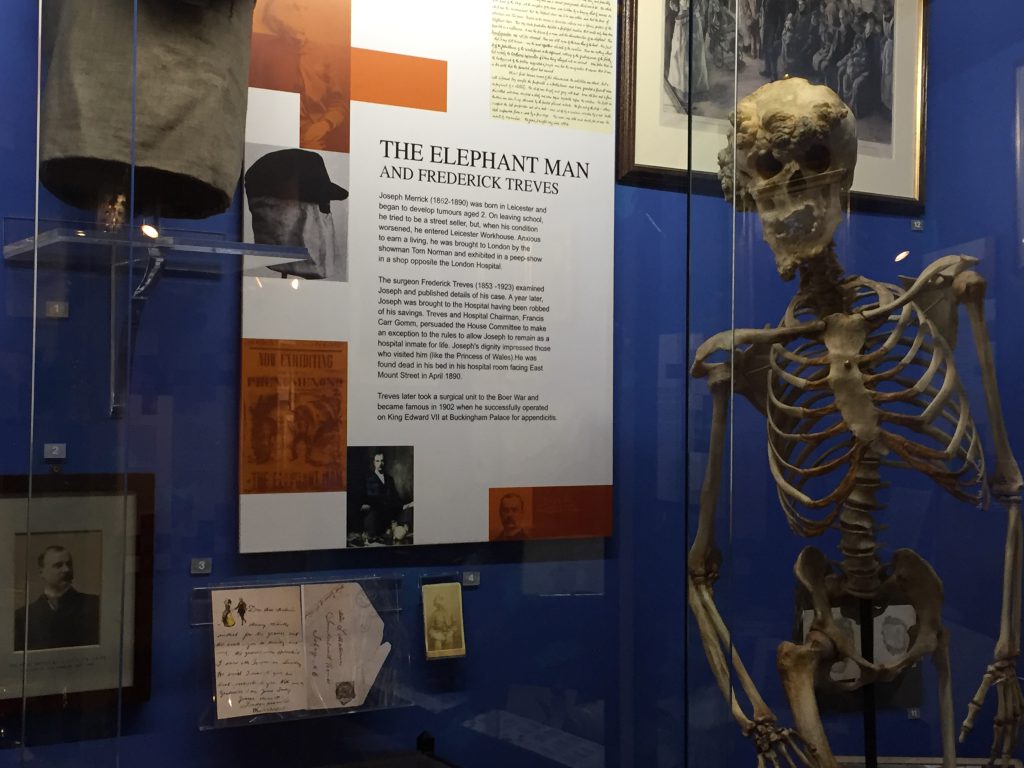

3. The Elephant Man Skeleton and Other Artefacts

Joseph Merrick, better known in popular culture as the “Elephant Man”, is probably the London Hospital’s best-known patient. Born in Leicester, Merrick was about five years old when he began developing signs of what is thought today to be Proteus Syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes overgrowth of bones, tissue and skin. As he grew older, his deformities prevented him from being able to hold down jobs. He spent some time in the workhouse in Leicester before joining San Torr’s traveling freak show and exploiting his body for money. During this time he was displayed for a brief period in a penny gaff shop in the Whitchapel Road, just opposite the London Hospital. There he became acquainted with eminent surgeon Frederick Treves, who later became Merrick’s saving grace.

While touring Belgium, Merrick was robbed and left destitute. He managed to make his way back to London where he was mobbed at Liverpool Street Station. Policemen who came to his rescue found Treve’s card in Merrick’s coat pocket and alerted the surgeon. In the 19th century, the London Hospital did not accommodate long-term patients, but Treves thought Merrick a special case. He appealed to readers of The Times for money to pay for Joseph to stay on as a permanent patient. An outpouring of public support allowed Merrick to live out the remaining six years of his life in a room facing Bedstead Square. There he was visited by many notable figures of the late-19th century, including Princess Alexandra, and became a celebrity in his own right.

On display in the Royal London Hospital Museum is a replica of Merrick’s skeleton (the real one is still held by the medical school, but is not on public display) as well as the hat and veil he wore in public. The objects are further contextualized by a documentary narrated by John Hurt — without a doubt the most popular video to museum visitors. Through them we get a better sense of Joseph’s life and his treatment at the hospital. And they allow us to discuss other issues such as ethics, disability, and Merrick’s important place in the history of medicine.

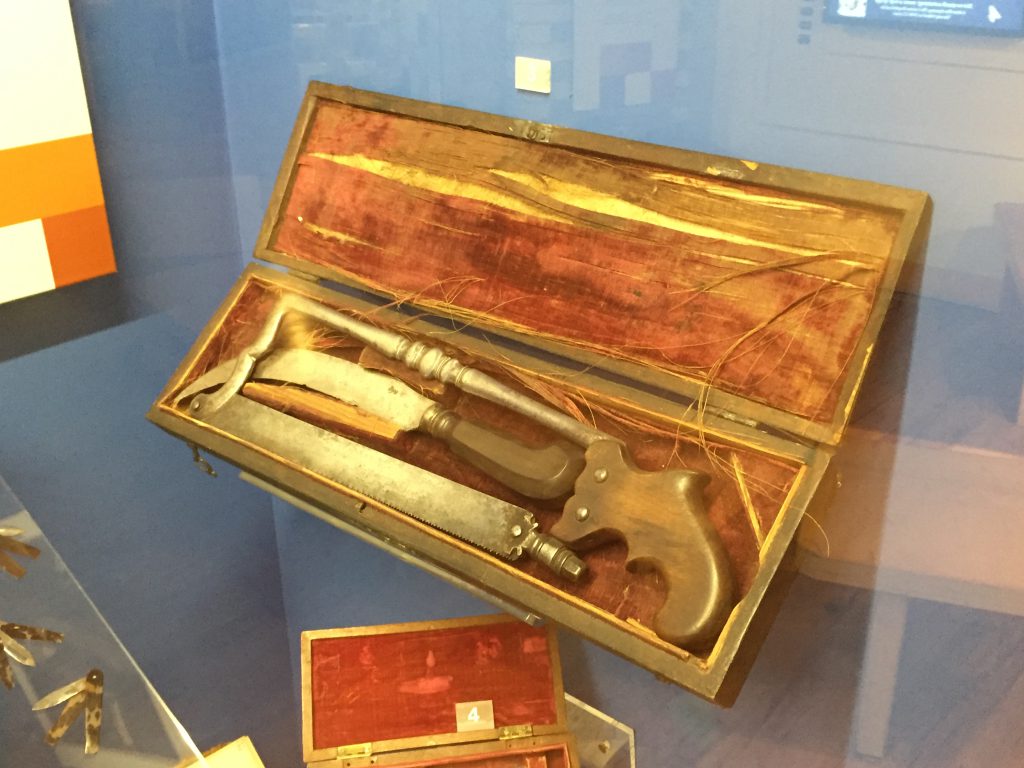

4. 18th Century Amputation Set

Surgeon William Blizard co-founded the Medical College at the London Hospital in 1785 – the first of its kind in the UK – and gained a reputation as a respected teacher in the operating theatre. This amputation set, containing a bone saw and curved dismembering knife, is believed to have belonged to him. Before anesthesia and antisepsis, surgery was a very dirty, painful and deadly business. If the operation didn’t kill you outright, infection probably would. Looking at these instruments, it’s no wonder people considered surgery as a last resort.

5: Viscount Knutsford's Giant Hearing Aid

Oh, how times have changed during the past century. This fascinating object that looks like a mix between an old telephone and a boom box is actually a hearing aid that belonged to Sydney George Holland, 2nd Viscount Knutsford. Knutsford, who was rendered mostly deaf in a road accident in 1915, served as the Chairman of the London Hospital from 1896 to 1931. The hearing aid was made by Hutchinson Acoustic in New York and contains four microphones, no doubt an important feature that ensured Knutsford didn’t miss any important details when conversing about the future of England’s largest hospital.

The Royal London Hospital Museum is open Tuesday-Friday, 10am-4:30pm // Located in the crypt of St Philips Church, Newark Street, Whitechapel